Nara Roesler São Paulo is pleased to present Star Noise, a group exhibition curated by Luis Pérez-Oramas and the Nara Roesler Curatorial Project. The show brings together works by Abraham Palatnik, Amelia Toledo, Artur Lescher, Brígida Baltar, Bruno Dunley, Cao Guimarães, Heinz Mack, Julio Le Parc, Laura Vinci, Mônica Ventura, Paulo Bruscky, Rodolpho Parigi, Tomás Saraceno, and Tomie Ohtake.

According to the curators, the works in Star Noise form a metaphorical constellation that suggests the world of artistic forms might be understood in terms of resonant “fields,” akin to the reality unveiled to us by physics. These would be fields of “figurability,” where forms never cease to emerge, each carrying within it the resonance of other forms—a continuous exercise in updating the figural energy that constitutes them and is constantly shifting and transfiguring.

The starting point for the exhibition is the “music of the stars,” first heard, identified, and recorded on September 16, 1932, at 7:10 p.m., in the fields of New Jersey by Karl Jansky (1905–1950), a physicist and engineer specializing in radio waves. Working for Bell Telephone Laboratories, Jansky was tasked with investigating sources of static interference in transatlantic radiotelephone communications. To do so, he built a radio wave receiver and, over three years, identified three types of static: nearby thunderstorms, distant storms, and what he described as “a persistent hiss, also of static origin, whose source was unknown.” Using his rotating antenna, Jansky was able to determine the direction of these signals. The strange hiss occurred every 23 hours and 56 minutes—four minutes less than a solar day—corresponding to the duration of a sidereal day. The strongest signal, recorded on September 16, 1932, led him to suggest that its source was not within our solar system, but rather from the center of the Milky Way, in the constellation Sagittarius. A few days later, Jansky confirmed that the radio waves he had detected indeed came from the “center of gravity of the galaxy.”

Years later, in 1974, at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Bruce Balick and Robert Brown discovered the object at the center of the Milky Way from which the hiss originated: Sagittarius A*, the immense black hole 4.3 million times more massive than the sun, the result of a stellar collapse.

The noise of the stars is the faint hiss of a sidereal past—the trace of original holocausts—that first reached us through Jansky’s antenna. Since then, other faint songs have been recorded: background cosmic resonances, or more recently, the subtle murmur of two massive black holes collapsing billions of years away—confirmation that gravitational waves exist in a space-time curved by the effect of astral masses. Yet even the most experienced scientists do not know what happens inside a black hole. Some believe that space and time may in fact dissolve there, losing all orientation.

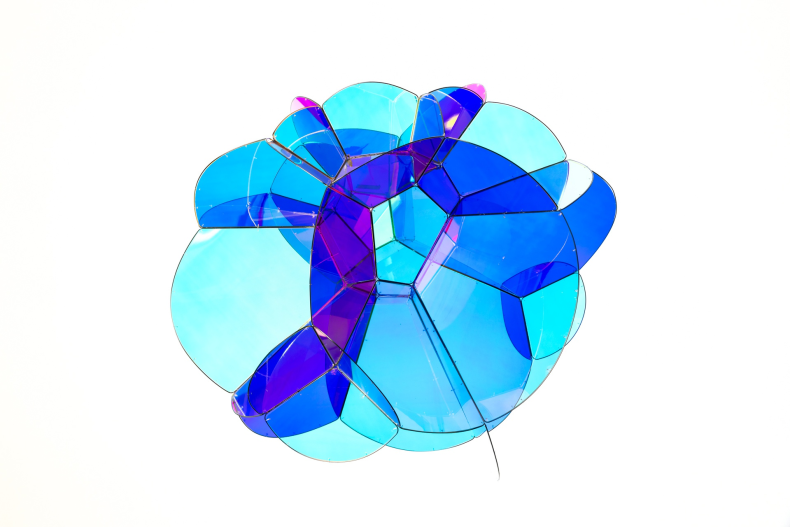

Drawing from works by Laura Vinci, Abraham Palatnik, Tomás Saraceno, Tomie Ohtake, Bruno Dunley, Mônica Ventura, Artur Lescher, Cao Guimarães, Paulo Bruscky, Rodolpho Parigi, and Julio Le Parc, the exhibition seeks to suggest an analogous scene—one in which artworks act as objects that, like Jansky’s antennas, capture background resonances from their own figural fields. Whether by mimicking the appearance of technical devices (Saraceno, Vinci, Ventura, Lescher); presenting compositions that resemble representations or records of cosmic resonance (Le Parc, Dunley, Palatnik, Ohtake, Parigi); or including, with ironic undertones, references to radios and radio antennas (Guimarães, Bruscky), these works evoke the interplay between form and resonance, technology and metaphor.