Tomie Ohtake (1913–2015) was born in Kyoto, Japan, and moved to Brazil in 1936, where she became one of the main representatives of abstract art in the country. Her career as an artist began at the age of 37, when she became a member of the Seibi group, which brought together artists of Japanese descent in Brazil. In the late 1950s, leaving behind an initial phase of figurative studies in painting, she immersed herself into abstract explorations.

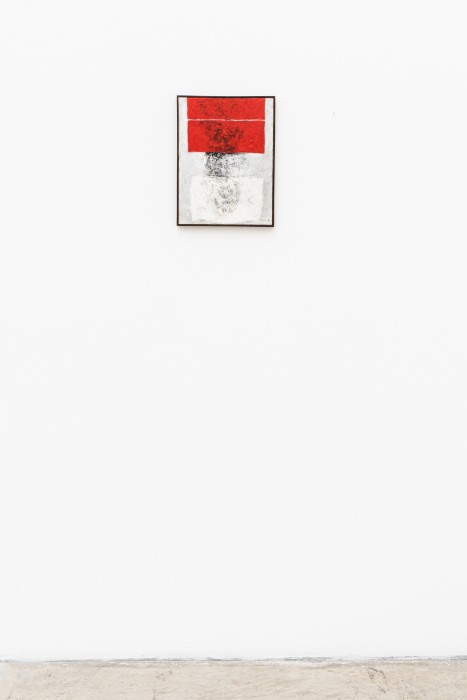

Tomie Ohtake’s 1964 painting Sem Título [Untitled] was created following a period of emblematic experimentations that were coined by art critic Mario Pedrosa as blind paintings, marking the artist’s initial experiments in abstraction. In these works, the artist would blindfold herself and paint abstract shapes characterized by spontaneity and fluidity; Sem título—being subsequent to this phase—displays remnants of an impulsive process, entwined with newfound geometric and structured forms. Sem Título embodies Ohtake’s investigative oscillation between abstraction’s possibilities—it displays condensed, defined shapes, dense colors, a distinct use of a foreground and a background while the outlines remain blurred, the shapes slanted and the whole appears ripped, as if a page had been torn. Interestingly, at that point in time, the artist had begun to produce small-scale studies using colored paper from magazines which she literally tore with her hands. Ohtake would rip shapes from publications and juxtapose them into compositions, then transposing them into large-format paintings.

As suggested by curator Paulo Miyada, the process became Ohtake’s way of dealing with the instantaneity of gesture and infusing the entire painting process with both chance and control. He notably wrote: ‘Paying close attention to the artist’s studies is, currently, a way to tap into the ingenuity with which she approached planning and unpredictability in her pictorial practice—while not denying the direct character of her painting. As a result, some of the recurrent polarities in the understanding of Brazilian painting from that period, such as the dichotomous polarization between geometric calculation and expressive gesture, can be elaborated anew, when considering Ohtake as a landmark of invention and freedom.’ Sem Título captures the artist’s lifelong strive to entwine allegedly incompatible practices, with an experimentation pulled by both extemporaneity and rationalist principles. In Ohtake’s own words, ‘A picture is not a thing, but a movement, it could be before, it could be after.’