Beginning on August 13, a unique portion of Antonio Dias’ multifaceted production will be revisited: his papers from Nepal, to be shown in Brazil for the first time. The exhibit Papéis do Nepal 1977-1986 will run until September 26 at Galeria Nara Roesler in Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro, offering in-depth insight into the universe of this household name, affording a new vision of the whole of his work.

Through his plurality of themes and processes, Dias evidences his refusal to adopt a single perspective of art production, preventing viewers from taking comfort in easy interpretations of his work. In the words of Italian art historian Sandro Sprocatti, Dias’ oeuvre projects “an anti-perspective situation par excellence, since it denies the exclusivity of one single vantage point, not only due to the representational instability (the substantial ambiguity of sign and space) but above all because it implies the plurality of conditions for enjoyment, i.e. the existential conditions the observer has in relation to others.”

The papers featured in the show were made during a trip Dias took to Nepal in 1977, to learn how to make handmade paper. The Nepal phase is a departure from the artist’s prior work, which had a strong conceptual leaning, used then-fledgling media like video, and created a visual lexicon that encompassed pop elements, geometrical planes defined by color and words.

Systematically repeated and scrambled within itself, this repertoire questioned the character of social convention and artistic institution as a producer of coded, clearly divided meanings, validated by an international system of insertion and representativeness to which the regional must submit – made evident in the artworks’ English titles, as in the famed The Illustration of Art series.

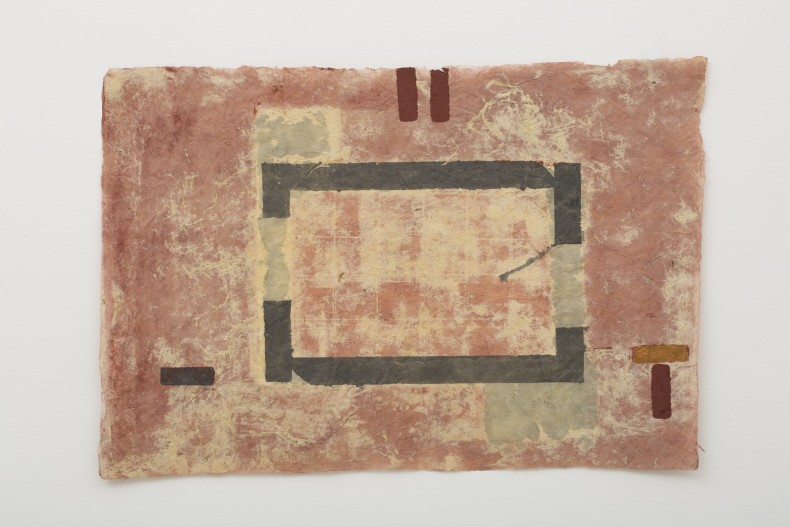

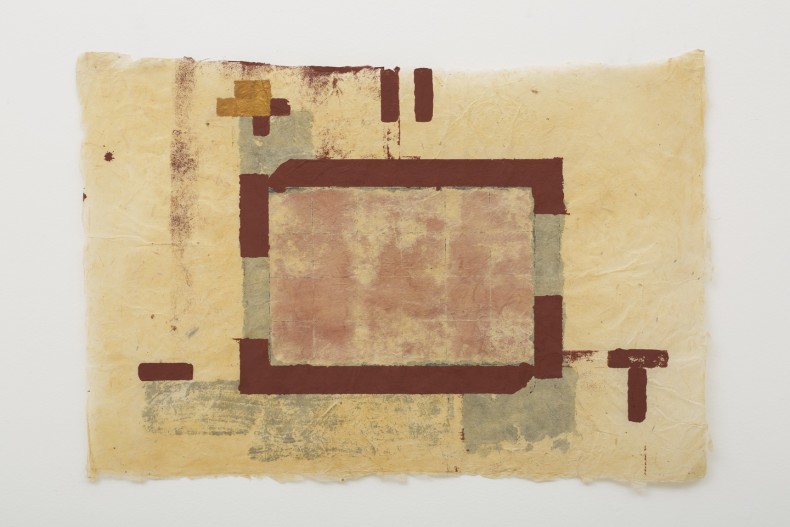

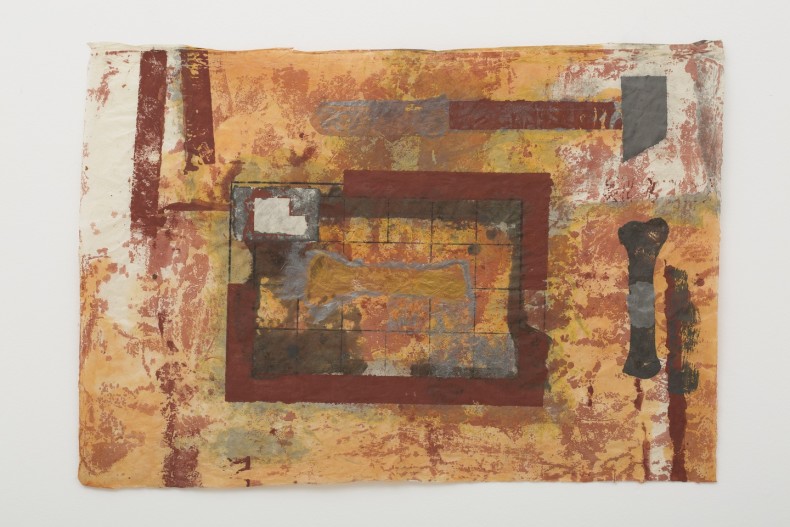

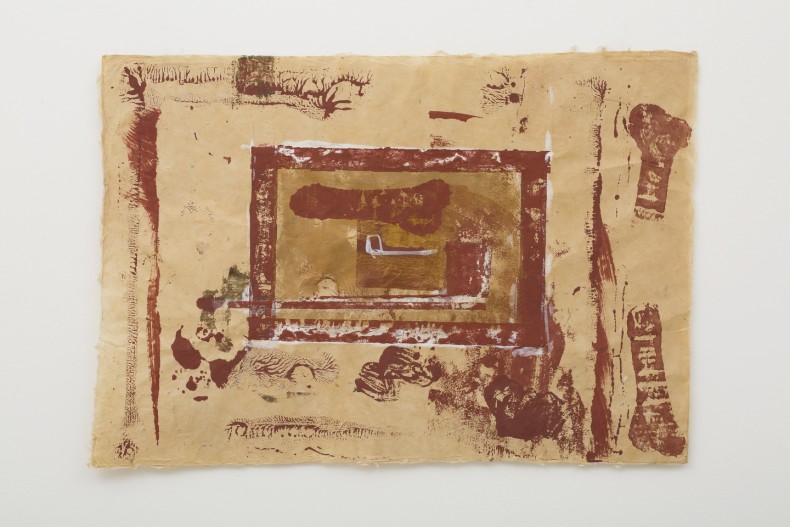

Much more than providing a medium, the large geometrical planes of handmade paper are artworks in their own right. Their colors stem from the addition, during manufacturing, of natural elements – like tea, earth, ashes and curry –, incorporating the production process as a component and an additional signifier of the pieces. Created jointly with artisans in a Nepalese paper factory, they subvert the issue of authorial unity in their genesis and even their titles, given by some of the workmen, like Niranjanirakhar.

Or, as the artist himself put it in an interview, “What interests me the most is the connection between the production of this work and its producers... While they labored materially in production, some of them also imprinted a symbolical reading onto the product.”

The Nepalese word Niranjanirakhar, which means Nothing, is a good synthesis of the ambivalence of meanings contained in this set of works. While their post-conceptual and procedural premise reiterates the need for the spectator to build significance, eliciting awareness and an active stance that goes beyond the imagetic surface of the artworks, their silence carries a near-mystical character, due to their own imperfect, organic materiality. And then there is the contamination of significance by territoriality, a theme the artist holds dear.

It is worth quoting Sandro Sprocatti again: “In both cases, figures ‘imported’ from the artist’s past works take on new meanings when in touch with the cultural sphere that witnessed their birth. As a result, the piece (also understood as work) becomes endowed with a symbolical depth that is at once improbable and exact. Likewise, the post-conceptual syntax of the installations finds new reasons of pertinence inside a mystic dimension that bears little connection with the West and its history.”